Original balustrade and die from Queen Square

Maker unknown, c.1732

Begun in 1728, Queen Square looked much different in the mid-eighteenth century than it does today, specifically its centre. The Square once contained a formal garden surrounding a tall obelisk with an elegant stone balustrade originally enclosing the central space. Made up of rectangular die and balusters, the balustrading was replaced by iron railings in the 1770s. This section of the balustrade was removed to a local garden in 1775 and its fragments were rescued and given to the Bath Preservation Trust in 1972.

These two rectangular die (that is, the two large rectangular blocks on either side of the balusters) have carved into them John Wood’s original plan for Queen Square; one has since been used as a sundial (left), while the other (right) records mason’s marks and the exact date on which the balustrading was removed: 8 August 1775.

In 2004, the Bath Stone Group kindly donated new stone and restored the balustrade to its original appearance.

Panorama of Bath

J.W. Allen, 1833 Oil on canvas

Allen’s Panorama was painted from Beechen Cliff, above the southern side of the city, and depicts Georgian Bath nestled in the valley created by the surrounding hills. Bath Abbey is clearly visible in the centre of the painting and the Royal Crescent can be seen in the middle ground to the far left.

Purchased with funds donated by:

- Eugene Cremetti Fund

- Bath City Council

- Victoria and Albert Purchase Grant Fund

The Bath City Model

Built on a 1:500 scale, this model took 10,000 hours to build. It was commissioned by the Bath Preservation Trust in 1965 and executed by Hugh Watson Associates with sponsorship from the Bath & Portland Stone Group.

At the time the model was commissioned, many of the city’s historic buildings were in danger of demolition, and a huge effort was made to preserve them. The buildings considered worthy of preservation were executed in detail in the model, so tiny architectural details were painstakingly depicted on the buildings deemed most historically important. This required considerable ingenuity: the columns in the Circus are actually pencil leads, and the acorns around the parapet are sanded-down hatpins.

In 1992, the principal new buildings were added with the assistance of the University of Bath.

Tool Chest Lid

Kindly lent by Jane Rees

This exquisite marquetry panel was undertaken in the 1790s as an example of a cabinetmaker’s skill. Often, as part of a joiner’s apprenticeships, he would construct a tool chest and decorate the inside of the chest lid. This would serve as a personal advertisement on completion of his seven-years’ apprenticeship.

In the eighteenth century, joiners designed and built wooden doors, windows, shutters, panelling, cupboards, and mouldings for interior spaces. Whereas carpenters used nails and dowels to stabilise their work, joiners used ‘scotch glue’, allowing them to create much more delicate and decorative work.

In the centre of this joiner’s lid, the joiner himself is depicted in his workshop, surrounded by the tools of his craft, including saws, moulding plans, and a compass. The large compass above his head and the intertwined compass and square on the left side of the workbench are symbols historically associated with freemasonry, which was accordingly associated with architecture and other building crafts.

Artist’s Box of Watercolours

With ‘Duffield’s Gallery of Engravings and Saloon of Fine Arts’ lithograph, 1829

This paint box displays the range of hues available in watercolour in the early nineteenth century. A similar box can be seen on the table in Duffield’s Gallery in Milsom Street. A lithograph on the underside of the lid depicts customers browsing in Duffield’s Gallery, suggesting that the box was bought there.

Certain pigments were very expensive and were a sign of personal wealth, thus painting and sketching became popular genteel pastimes in the eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries.

Hand-modelled plaster

By the middle of the eighteenth century, rooms were no longer wholly panelled in wood; instead they were plastered above the wooden dado. Plaster cornices had also replaced wooden cornices, as they were relatively easy to apply using special tools. Decorative wall applications could also be achieved rater easily using moulds. Plasterwork gained popularity during the eighteenth century due to the work of prominent designers and architects like Gringling Gibbons, Christopher Wren, and William Kent, who recreated Classical motifs in country houses using plaster. Some of Bath’s best preserved pasterwork is in the Assembly Rooms, build by John Wood the Younger in 1769.

This panel is an example of hand-modelled plasterwork, created by an artist without moulds. It was made by one of the craftsmen later employed on the restoration of Prior Park after a devastating fire in 1991. Often, hand-modelling was reserved for decorative floral designs like this one, or for more intricate depictions of mythological of hunting scenes.

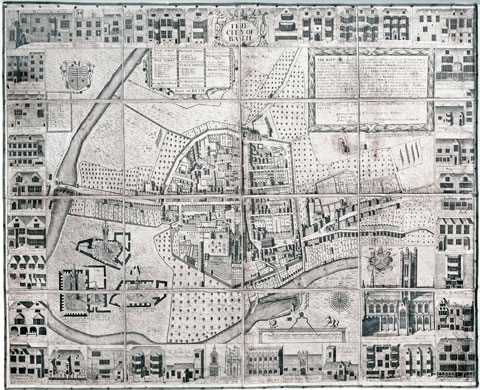

Map of Bath by Joseph Gilmore

1694

The Gilmore map of 1694 shows Bath as a city largely contained within its medieval walls, with a population of about 3,000. The map also advertises some of the city’s amenities, with many inns and lodging houses illustrated in the border. It captures the city in the late seventeenth century, just before the transformation of Georgian Bath was about to begin. A prominent illustration of Bath Abbey is featured in the lower right corner and a list of inns organised by street is just below the upper border, slightly to the left. This map is orientated with North to the right.

Stone Acorn from the parapet of the Circus

Gift from Mrs Jane Swift and Brown Morton III

This acorn was taken from the parapet of the Circus. By placing acorns along the top of the Circus, John Wood was making references to the legend of the founding of Bath following Bladud’s discovery of the healing hot waters; his leprous pigs were cured when they discovered the hot spring while foraging for acorns. The acorn also references Wood’s fascination with the Druids, who were the ‘Princes of the Hollow Oak’.

In planning the new Georgian city, Wood wanted to give England its own version of Rom, and based much of his new projects in English folklore and heritage. The Circus (meant to echo Rome’s Circus Maximus) was built to Wood’s measurements of Stonehenge as a temple to the sun, and the Royal Crescent just down Brock Street was conceived as a temple to the moon.

Surveyor’s Tools

Theodolite (pictured): Brass, late eighteenth century, made by John King of Bristol

Surveyor’s Level: Mahogany and box, late eighteenth century

Architectural drawing instruments: Brass and ivory, mahogany case

Made in John Braham’s workshop, Bristol, c.1830

The title of ‘architect’ was a prestigious one in the eighteenth century, At the time, there was no professional qualification for architects, but one did have to prove his knowledge of the principles of Classical style, geometry, mathematics, and sound construction to acquire a good reputation. Often, architects acted as surveyors as well; they had to survey land, lay out plots, ensure that builders were doing the work agreed upon, settle disputes, and decide each builder’s proportion of shared costs.

Surveying, as with other specialised professions, required specific tools:

- A theodolite (like the one picture above) is a telescope mounted on a tripod or pole and then placed on a firm base. It was used to calculate angles so that through trigonometry the surveyor could measure the distance and height of a building.

- The surveyor’s level is a simpler instrument than the theodolite because because it cannot measure angles. it was employed in measuring gradients and setting out levels and was used when surveying land and constructing drains or roads.

- Architects used fine brass instruments like those in the collection to render plans and elevations of their projects.